Jesper reads ... Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka :: Novels, stories, letters

Welcome to Jesper TTS, your first AI-powered audio voice fully dedicated to the powerful literary work of Franz Kafka. Using cutting-edge technology, Jesper TTS brings Kafka's profound narratives and complex characters to life by reproducing them in a clear, expressive and captivating way. Whether you're a passionate Kafka fan or discovering his works for the first time, Jesper TTS offers you a unique and immersive listening experience that redefines the boundaries between text and listener. Immerse yourself in Kafka's world like never before - experience his stories in a convenient and accessible way, anytime, anywhere.

Coming soon as an audiobook

- America

- Aphorisms. Notes from 1920 - Paralipomena - Reflections on sin, suffering, hope and the true path

- Blumfeld, an elderly bachelor

- Letter to Max Brod. Testament

- Letter to the father

- Letters to Ottla and the family. Excerpts

- The castle

- The construction

- The Crypt Keeper

- The process

- The Eight Octave Books

- The Metamorphosis - Gutenberg Edition 16 : https://www.projekt-gutenberg.org/kafka/verwandl/verwandl.html

- Stories I

- Stories II

- Fragments from booklets and loose sheets

- In the penal colony

- Diaries 1910-1923

Welcome to Kafka In-Spaces, an innovative dimension of the listening experience that aims to bring the profound literary works of Franz Kafka closer to a modern audience. Using the latest sound generation and audio technology, we aim to transform Kafka's complex narratives into vivid, atmospheric sound experiences that captivate, engage and expand the listener's understanding of this unique author's themes.

Kafka In-Spaces weaves Franz Kafka's original texts with ambient sounds, subtle - yes, subcutaneous music, and spatial sound effects that immerse the listener in a labyrinthine web of Kafka's inner worlds. Each story is carefully crafted with sound elements that enhance the surreal and often oppressive atmospheres of his texts. From the eerie echoes of footsteps in a labyrinthine courthouse in The Trial to the oppressive clank of the torture machine in In the Penal Colony, our audio environments are carefully designed to complement Kafka's tone and mood.

The works of Franz Kafka explore themes such as alienation, existential angst, and bureaucratic absurdity - themes that are still relevant in our current times. Yet Kafka's dense text and abstract ideas can be challenging. Our immersive audio complex makes Kafka's themes more accessible and relatable, taking listeners on a captivating and thought-provoking journey through his labyrinthine universe. We believe that by enhancing the sensory experience, we can open Kafka's works to a wider audience, inviting more people to sensitively and intellectually explore his influential ideas.

Our team consists of sound designers, musicians and literary experts, all united by a passion for classical literature and audiovisual storytelling. We use our diverse skills to create a unique acoustic journey that respects Kafka's original texts in every way and brings them to life once again in all authenticity for contemporary listeners.

Join us as we redefine the way classic literature is enjoyed. Kafka In-Spaces is not just an audiobook; it's an adventure trip into the heart of the human experience. Whether you're a lifelong Kafka fan or encountering his work as a newcomer, prepare to experience his stories in a suitably extraordinary way. Coming soon to platforms like Spotify, Audible, and Apple Podcasts - subscribe today to be the first to delve into Kafka's labyrinthine world.

Franz Kafka

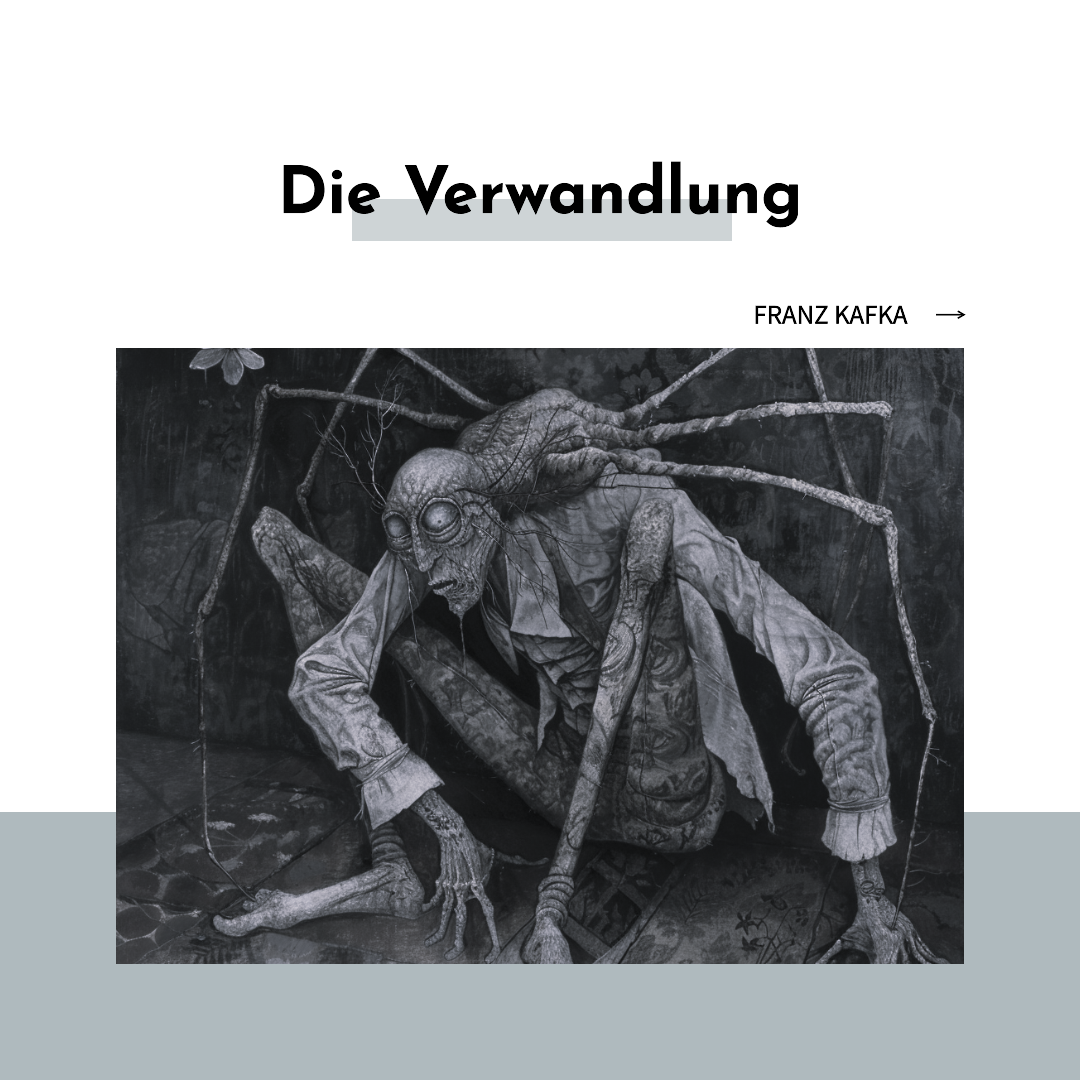

The transformation

When Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a monstrous vermin. He lay on his armour-like back and, if he lifted his head a little, he could see his bulging, brown belly, divided by arched stiffeners, at the height of which the bedclothes could barely stay in place, ready to slide off completely. His many legs, pitifully thin compared to his usual size, flickered helplessly before his eyes.

"What has happened to me?" he thought. It was no dream. His room, a proper human room, just a little too small, lay quietly between the four familiar walls. Above the table, on which an unpacked collection of cloth samples was spread out - Samsa was a travelling salesman - hung the picture that he had recently cut out of an illustrated magazine and put in a pretty, gilded frame. It showed a lady wearing a fur hat and fur boa, sitting upright and raising a heavy fur muff, in which her whole forearm had disappeared, towards the viewer.

Gregor then turned his gaze to the window, and the dull weather - you could hear raindrops hitting the windowpane - made him quite melancholy. "How about if I sleep a little longer and forget all this nonsense," he thought, but that was completely impossible, because he was used to sleeping on his right side, but in his current state he couldn't get into that position. No matter how hard he threw himself onto his right side, he always rocked back onto his back. He tried it a hundred times, closing his eyes so he didn't have to see his thrashing legs, and only stopped when he began to feel a slight, dull pain in his side that he had never felt before.

"Oh God," he thought, "what a strenuous profession I have chosen! Day in, day out on the road. The business stress is much greater than the actual business at home, and on top of that I have to deal with the torment of traveling, the worries about train connections, the irregular, bad food, constantly changing, never lasting, never warm human contact. The devil take it all!" He felt a slight itch on the top of his stomach; he slowly moved closer to the bedpost on his back so he could raise his head better; he found the itchy spot, which was covered with lots of little white dots that he couldn't identify; and wanted to touch the spot with one leg, but immediately pulled it back because the touch sent a shiver of cold over him.

He slipped back into his previous position. "Getting up so early," he thought, "makes one quite stupid. One must have his sleep. Other travelers live like harem women. For example, when I go back to the inn in the course of the morning to sign over the orders I have received, these gentlemen are only sitting down to breakfast. I should try that with my boss; I would be thrown out on the spot. Who knows, by the way, whether that would not be very good for me. If I had not held back because of my parents, I would have resigned long ago, I would have gone up to the boss and told him my heartfelt opinion. He would have fallen off the desk! It is also a strange way of sitting on the desk and talking down to the employee, who, moreover, has to get very close because of the boss's hard of hearing. Well, hope is not entirely lost; Once I have enough money to pay off my parents' debt to him - it will probably take another five or six years - I will definitely do it. Then the big deal will be made. For now, though, I have to get up because my train leaves at five."

And he looked over at the alarm clock ticking on the cabinet. "Heavenly Father!" he thought. It was half past six and the hands were moving steadily forward, it was even half past, it was already approaching three-quarters. Hadn't the alarm clock rung? From the bed you could see that it was correctly set for four o'clock; it had certainly rung. Yes, but was it possible to sleep through that furniture-shaking ringing? Well, he hadn't slept peacefully, but probably all the more soundly. But what should he do now? The next train left at seven o'clock; to catch it he would have had to hurry like crazy, and the collection hadn't been packed yet, and he himself didn't feel particularly fresh or agile. And even if he caught up with the train, a thunderstorm from the boss was inevitable, because the clerk had been waiting for the five o'clock train and had long since reported his absence. He was a creature of the boss, without a backbone or sense. What if he called in sick? That would be extremely embarrassing and suspicious, because Gregor had never been sick once during his five years of service. The boss would certainly come with the health insurance doctor, reproach the parents for their lazy son and cut off all objections by pointing out the health insurance doctor, who only sees people who are completely healthy but who are lazy. And would he be completely wrong in this case? Apart from a really unnecessary sleepiness after the long sleep, Gregor actually felt quite well and was even particularly hungry.

2

As he was thinking all this over in great haste, without being able to bring himself to leave the bed—the alarm clock had just struck a quarter to seven—there was a gentle knock on the door at the head of his bed.

"Gregor," called out - it was his mother - "it's a quarter to seven. Didn't you want to go away?" The soft voice! Gregor was startled when he heard his answering voice, which was unmistakably his old one, but which was mixed with an irrepressible, painful squeak, as if from below, which only left the words clear for the first moment, only to destroy them in the aftermath so that one did not know whether one had heard correctly. Gregor had wanted to answer in detail and explain everything, but in these circumstances he limited himself to saying: "Yes, yes, thank you mother, I'm already up." Because of the wooden door, the change in Gregor's voice was probably not noticeable outside, because his mother calmed down with this explanation and shuffled away. But the little conversation had made the other family members aware that Gregor was, contrary to expectations, still at home, and his father was already knocking on the side door, weakly but with his fist. "Gregor, Gregor," he called, "what is it?" And after a while he warned again in a deeper voice: "Gregor! Gregor!" But at the other side door his sister complained softly: "Gregor? Are you not well? Do you need anything?" Gregor answered both ways: "I'm finished," and tried to remove all the unusualness from his voice by pronouncing it very carefully and by inserting long pauses between the individual words. His father also returned to his breakfast, but his sister whispered: "Gregor, open up, I implore you." But Gregor had no intention of opening up, instead praising the caution he had acquired from traveling, of locking all doors at home at night.

First he wanted to get up quietly and undisturbed, get dressed and, above all, have breakfast, and only then think about what was next, because he realized that thinking about things in bed would not bring him to any sensible conclusion. He remembered that he had often felt some kind of slight pain in bed, perhaps caused by lying awkwardly, which turned out to be pure imagination when he got up, and he was curious to see how his current ideas would gradually dissipate. He had not the slightest doubt that the change in his voice was nothing more than the harbinger of a bad cold, an occupational disease of travelers.

Throwing off the blanket was quite easy; he only had to puff himself up a little and it fell off of its own accord. But after that it became difficult, especially because he was so incredibly broad. He would have needed arms and hands to pull himself up; instead he only had his many little legs, which were constantly moving in all sorts of different ways and which he could not control. If he tried to bend one of them, it would straighten up first; and if he finally managed to do what he wanted with that leg, all the others would work in the meantime, as if they had been set free, in extreme, painful excitement. "Don't waste any time in bed," Gregor said to himself.

At first he wanted to get out of bed with the lower part of his body, but this lower part, which he had not yet seen and of which he could not form a proper idea, proved to be too difficult to move; it went so slowly; and when at last, almost wildly, he pushed forward with all his strength, without considering, he had chosen the wrong direction, hit the lower bedpost violently, and the burning pain he felt taught him that the lower part of his body was perhaps the most sensitive at that moment.

He therefore tried to get his upper body out of the bed first and carefully turned his head towards the edge of the bed. This was easy and, despite its width and weight, the mass of his body slowly followed the turn of his head. But when he finally held his head outside the bed in the open air, he became afraid to continue in this way, because if he finally let himself fall like that, a miracle would have to happen if his head was not to be injured. And he could not lose consciousness at any cost at this time; he would rather stay in bed.

But when, after the same effort, he lay there again, sighing, as before, and again saw his little legs fighting against each other, perhaps even more violently, and could find no way of bringing peace and order to this arbitrary behavior, he told himself again that he could not possibly stay in bed, and that the most sensible thing to do was to sacrifice everything if there was even the slightest hope of getting out of bed. At the same time, however, he did not forget to remind himself from time to time that calm and quiet reflection was much better than desperate resolutions. At such moments he fixed his eyes as sharply as possible on the window, but unfortunately little confidence or cheer could be drawn from the sight of the morning mist, which even covered the other side of the narrow street. "It's already seven o'clock," he said to himself as the alarm clock struck again, "it's already seven o'clock, and there's still such a fog." And for a while he lay quietly, breathing weakly, as if he were perhaps expecting the complete silence to bring a return to real and natural circumstances.

3

But then he said to himself: "Before the clock strikes a quarter to eight, I absolutely must be completely out of bed. Besides, by then someone from the shop will come to ask for me, because the shop opens before seven o'clock." And he then set about rocking his body out of bed in a completely even manner. If he let himself fall out of bed in this way, his head, which he would raise sharply as he fell, would probably remain unharmed. His back seemed hard; it would probably be fine if he fell onto the carpet. His greatest concern was the loud noise that would be made, and which would probably cause, if not terror, then at least concern behind all the doors. But he had to risk it.

When Gregor was already halfway out of bed - the new method was more of a game than an effort, he only had to rock in jerks - it occurred to him how easy everything would be if someone came to help him. Two strong people - he thought of his father and the maid - would have been completely sufficient; they would only have had to put their arms under his arched back, pull him out of bed, bend down with the load and then just carefully allow him to swing over onto the floor, where his little legs would hopefully then make sense. Well, quite apart from the fact that the doors were locked, should he really have called for help? Despite all his distress, he could not suppress a smile at the thought.

He had already reached the point where he could hardly keep his balance if he rocked too hard, and very soon he had to make a final decision, because in five minutes it would be a quarter to eight when the doorbell rang. "That's someone from the business," he said to himself and almost froze, while his little legs danced all the more quickly. For a moment everything was quiet. "They're not opening," Gregor said to himself, caught up in some foolish hope. But then, of course, the maid walked firmly to the door and opened it, as always. Gregor only had to hear the visitor's first word of greeting and he knew who it was - the manager himself. Why was Gregor condemned to work for a company where the slightest oversight immediately aroused suspicion? Were all the employees scoundrels, was there not a single loyal, devoted person among them who, if he had not used even a few hours of the morning for business, would go mad with remorse and be virtually unable to get out of bed? Was it really not enough to have an apprentice ask questions - if this questioning was even necessary -, did the chief clerk have to come himself and thereby show the whole innocent family that the investigation of this suspicious matter could only be entrusted to the chief clerk's mind? And more as a result of the excitement that Gregor was put into by these considerations than as a result of a correct decision, he swung himself out of bed with all his might. There was a loud bang, but it was not a real crash. The fall was softened a little by the carpet, and his back was more elastic than Gregor had thought, which is where the not so noticeable dull sound came from. He had only not held his head carefully enough and hit it; he turned it and rubbed it on the carpet in anger and pain.

"Something fell in there," said the chief clerk in the next room on the left. Gregor tried to imagine whether something similar to what had happened to him today could happen to the chief clerk; one had to admit that it was possible. But as if to give a crude answer to this question, the chief clerk in the next room took a few determined steps and made his patent leather boots creak. From the next room on the right, the nurse whispered to Gregor: "Gregor, the chief clerk is here." "I know," said Gregor to himself; but he did not dare raise his voice loud enough for the nurse to hear.

"Gregor," said the father from the next room to the left, "the manager has come and is asking why you didn't leave on the early train. We don't know what to say to him. Incidentally, he also wants to speak to you personally. So please open the door. He will be kind enough to excuse the mess in the room."

"Good morning, Mr. Samsa," the manager called out in a friendly tone. "He's not feeling well," said the mother to the manager while the father was still talking at the door, "he's not feeling well, believe me, Mr. Manager. How else would Gregor miss a train! The boy has nothing on his mind but his business. I'm almost annoyed that he never goes out in the evenings; he's been in town for eight days, but he's been at home every evening. He sits at our table and quietly reads the newspaper or studies train schedules. It's a real diversion for him when he's busy doing fretwork. For example, in the course of two or three evenings he carved a small frame; you'll be amazed at how pretty it is; it's hanging in the room; you'll see it in a minute before Gregor opens the door. By the way, I'm glad you're here, Mr. Manager; we alone wouldn't have got Gregor to open the door; he's so stubborn; and he certainly is not well, although he denied it this morning."

"I'll be right there," said Gregor slowly and carefully, not moving so as not to miss a word of the conversation. "I can't explain it any other way, madam," said the manager, "I hope it's nothing serious. Although on the other hand I must say that we business people - unfortunately or fortunately, depending on who you are - often have to overcome a slight feeling of unease for business reasons." "So the manager can come in now?" asked the impatient father and knocked on the door again. "No," said Gregor. An awkward silence fell in the next room on the left, and in the next room on the right the sister began to sob.

4

Why didn't his sister go to the others? She had only just gotten out of bed and hadn't even started to get dressed. And why was she crying? Because he didn't get up and let the manager in, because he was in danger of losing his job and because the boss would then come after his parents again with the same old demands? Those were probably unnecessary worries for the time being. Gregor was still here and wasn't even thinking about leaving his family. At the moment he was probably lying there on the carpet and no one who knew his condition would seriously have asked him to let the manager in. But Gregor couldn't be sent away immediately because of this little act of impoliteness, for which a suitable excuse could easily be found later. And Gregor thought that it would be much more sensible to leave him alone now, instead of disturbing him with crying and talking. But it was precisely the uncertainty that was troubling the others and excusing their behavior.

"Mr. Samsa," the manager called out in a raised voice, "what's going on? You're barricading yourself in your room, answering only yes and no, causing your parents great, unnecessary worry and - just to mention this in passing - neglecting your business duties in a way that is actually unheard of. I'm speaking here on behalf of your parents and your boss and I'm asking you quite seriously for an immediate, clear explanation. I'm astonished, I'm astonished. I thought I knew you as a calm, reasonable person, and now you suddenly seem to want to start showing off your strange moods. The boss did suggest to me this morning a possible explanation for your neglect - it concerned the debt collection that you had recently been entrusted with - but I practically gave my word of honor that this explanation could not be correct. But now I see your incomprehensible stubbornness and I've completely lost all desire to do anything for you. And your position is by no means the most stable. I had originally intended to tell you all this in private, but since you are making me waste my time here, I don't know why your parents shouldn't hear about it too. Your performance of late has been very unsatisfactory; it is true that this is not the season for doing special business, we recognize that; but there is no such thing as a season for not doing business, Mr. Samsa, there must not be one."

"But Mr. Manager," cried Gregor, beside himself, forgetting everything else in his excitement, "I'll get up right away, right now. A slight feeling of indisposition, a dizzy spell, prevented me from getting up. I'm still lying in bed. But now I'm feeling quite refreshed again. I'm just getting out of bed. Just a moment's patience! I'm not as well as I thought. But I'm already feeling better. How can something like that happen to a person like that! I was fine yesterday evening, my parents know that, or rather, I had a slight premonition yesterday evening. It should have been obvious. Why didn't I tell the office? But you always think that you'll get over the illness without having to stay at home. Mr. Manager! Go easy on my parents! There's no reason for all the reproaches you're making against me now; I haven't been told a word about it. Perhaps you haven't read the last orders I sent. By the way, I'm leaving on the eight o'clock train; the few hours of rest have strengthened me. Don't delay, Mr. Manager; I'll be at work myself in a minute, and please be so kind as to say so and to recommend me to the boss!'

And while Gregor was uttering all this hastily and hardly knowing what he was saying, he had approached the box easily, probably as a result of the practice he had already gained in bed, and was now trying to pull himself up against it. He really wanted to open the door, really wanted to be seen and speak to the chief clerk; he was eager to find out what the others, who were now so eager to see him, would say when they saw him. If they were frightened, then Gregor would no longer have any responsibility and could be calm. But if they accepted everything calmly, then he too would have no reason to get upset and, if he hurried, he could actually be at the station by eight o'clock.

At first he slipped a few times off the smooth box, but finally he gave himself one last push and stood upright; he no longer paid any attention to the pain in his abdomen, however much it burned. He then let himself fall against the back of a nearby chair, holding on to the edges with his little legs. With this he had also gained control of himself and fell silent, for now he could listen to the chief clerk.

"Did you understand a single word?" the manager asked the parents. "He's not making a fool of us, is he?" "For God's sake," the mother cried, already crying, "he may be seriously ill and we're tormenting him. Grete! Grete!" she then screamed. "Mother?" the sister called from the other side. They communicated through Gregor's room. "You must go to the doctor immediately. Gregor is ill. Quickly, to the doctor. Did you hear Gregor talking?" "That was an animal voice," said the manager, noticeably quiet compared to the mother's screaming.

"Anna! Anna!" called the father through the hall into the kitchen, clapping his hands, "get a locksmith immediately!" And the two girls ran through the hall with their skirts swishing - how had their sister gotten dressed so quickly? - and tore open the door to the apartment. The door was not heard slamming; they had probably left it open, as is usual in apartments where a great misfortune has occurred.

5

Gregor had become much calmer. His words were no longer understood, although they had seemed clear enough to him, clearer than before, perhaps as a result of his ears getting used to them. But at least people now believed that there was something wrong with him and were prepared to help him. The confidence and certainty with which the first instructions had been given did him good. He felt included in the human circle again and hoped for great and surprising achievements from both the doctor and the locksmith, without really distinguishing them. In order to make his voice as clear as possible for the crucial discussions that were approaching, he coughed a little, although he tried to do so very quietly, since even this noise might sound different from a human cough, which he no longer dared to decide for himself. In the next room it had become completely quiet. Perhaps his parents were sitting at the table with the manager and whispering, perhaps everyone was leaning against the door and listening.

Gregor slowly pushed himself and the chair towards the door, let go of it, threw himself against the door, held himself upright against it - the pads of his little legs had a little glue on them - and rested there for a moment from the exertion. Then he set about turning the key in the lock with his mouth. Unfortunately, it seemed that he had no real teeth - how was he supposed to hold the key with? - but his jaws were very strong; with their help he actually got the key moving and didn't pay any attention to the fact that he was undoubtedly doing himself some kind of damage, because a brown liquid came out of his mouth, flowed over the key and dripped onto the floor.

"Just listen," said the manager in the next room, "he's turning the key." That was a great encouragement for Gregor; but everyone should have called out to him, including his father and mother: "Come on, Gregor," they should have called out, "just get closer, get closer to the lock!" And imagining that everyone was watching his efforts with excitement, he clenched his teeth senselessly on the key with all the strength he could muster. As the key continued to turn, he danced around the lock; now he only held himself upright with his mouth, and as needed he hung on to the key or pressed it down again with the full weight of his body. The brighter sound of the lock finally snapping back literally woke Gregor up. With a sigh of relief, he said to himself: "So I didn't need the locksmith," and laid his head on the handle to open the door completely.

Since he had to open the door in this way, it was actually already quite wide open and he himself could not yet be seen. He had to turn slowly around one of the doors, and very carefully, if he did not want to fall clumsily onto his back just before entering the room. He was still busy with that difficult movement and had no time to pay attention to anything else when he heard the chief clerk let out a loud "Oh!" - it sounded like the wind roaring and now he saw him too, as he, who was closest to the door, pressed his hand against his open mouth and slowly backed away as if an invisible, constant force were driving him away. The mother - she was standing here despite the presence of the chief clerk with her hair still loose and standing on end from the night - first looked at her father with folded hands, then took two steps towards Gregor and fell down in the middle of her skirts, which spread out around her, her face sunk completely untraceable onto her chest. The father clenched his fist with a hostile expression, as if he wanted to push Gregor back into his room, then looked uncertainly around the living room, then shaded his eyes with his hands and cried until his powerful chest shook.

Gregor did not enter the room at all, but leaned against the locked door from the inside, so that only half of his body was visible, and above that his head, which was tilted to the side, was visible, peering over at the others. It had become much lighter in the meantime; on the other side of the street there was a clear section of the endless, grey-black building opposite - it was a hospital - with its regular windows breaking through the front; the rain was still falling, but only in large, individual drops that were visible and literally thrown down to the ground one by one. The breakfast dishes were on the table in abundance, because for his father breakfast was the most important meal of the day, which he would drag out for hours while reading various newspapers. Right on the opposite wall hung a photograph of Gregor from his military days, showing him as a lieutenant, his hand on his sword, smiling carefree, demanding respect for his bearing and uniform. The door to the anteroom was open, and since the apartment door was also open, one could see the forecourt of the apartment and the beginning of the stairs leading down.

"Well," said Gregor, well aware that he was the only one who had kept his cool, "I'm going to get dressed, pack up the collection and leave. Will you, will you let me leave? Well, Mr. Manager, you see, I'm not stubborn and I like to work; traveling is difficult, but I couldn't live without traveling. Where are you going, Mr. Manager? To the store? Yes? Will you report everything truthfully? One can be unable to work at the moment, but then it's just the right time to remember one's previous achievements and to consider that later, once the obstacle has been removed, one will certainly work even more diligently and concentratedly. I owe so much to the boss, you know that very well. On the other hand, I'm worried about my parents and my sister. I'm in a tight spot, but I'll work my way out of it. But don't make it more difficult for me than it already is. Take my side in business! People don't like travelers, I know. People think they earn a fortune and lead a good life. There is no particular reason to think this prejudice through. But you, Mr. Manager, you have a better overview of the situation than the rest of the staff, and even, in confidence, a better overview than the boss himself, who, in his capacity as an entrepreneur, can easily be swayed in his judgment to the detriment of an employee. You also know very well that the traveler, who is away from work almost the whole year, can easily become a victim of gossip, coincidences and groundless complaints, against which it is quite impossible for him to defend himself, since he usually hears nothing about them and only when he returns home exhausted from a trip does he experience the terrible consequences, the causes of which are no longer clear. Mr. Manager, don't leave without saying a word to me that shows me that you agree with me at least to a small extent!'

6

But the chief clerk had already turned away at Gregor's first words, and only looked back at Gregor over his twitching shoulder, lips pursed. And during Gregor's speech he did not stand still for a moment, but retreated towards the door, without taking his eyes off Gregor, but very gradually, as if there was a secret prohibition against leaving the room. He was already in the anteroom, and after the sudden movement with which he pulled his foot out of the living room for the last time, one would have thought he had just burned the sole of his foot. In the anteroom, however, he stretched his right hand far away from him toward the stairs, as if an almost supernatural salvation were waiting for him there.

Gregor realized that he could not let the manager leave in this mood if he did not want to endanger his position in the business to the extreme. His parents did not understand all this very well; over the years they had formed the conviction that Gregor was provided for in this business for life, and on top of that they were now so busy with their immediate worries that they had lost all foresight. But Gregor had this foresight. The manager had to be held on to, calmed down, convinced and finally won over; the future of Gregor and his family depended on it! If only his sister had been here! She was clever; she had already cried when Gregor was still lying quietly on his back. And the manager, this lady friend, would certainly have let her guide him; she would have closed the door to the apartment and talked him out of his fear in the hallway. But his sister was not there, Gregor himself had to act.

And without thinking that he was not yet aware of his current ability to move, without even thinking that his speech might not have been understood again - indeed, probably - he left the door, pushed himself through the opening, wanted to go to the manager, who was already holding on to the railing of the forecourt with both hands in a ridiculous way, but immediately fell down on his many little legs with a little cry, searching for something to hold on to. He had hardly done that when he felt physical well-being for the first time that morning; his little legs had solid ground beneath them; they obeyed him completely, he noticed to his delight; they even strove to carry him wherever he wanted; and he already believed that the final improvement of all suffering was imminent. But at the same moment, as he lay there, rocking with restrained emotion, not far from his mother, directly opposite her, she, who seemed so absorbed in herself, suddenly jumped up, her arms outstretched, her fingers spread, calling out: "Help, for God's sake, help!", bowed her head as if she wanted to see Gregor better, but, contrary to this, ran senselessly backwards; she had forgotten that the table was set behind her; when she reached him, she sat down hastily on him, as if distracted; and did not seem to notice at all that coffee was pouring out of the overturned large pot onto the carpet next to her.

"Mother, mother," said Gregor quietly, looking up at her. The chief clerk had completely slipped his mind for a moment; however, he could not resist snapping his jaws into the void several times when he saw the coffee pouring out of the cup. At this, his mother screamed again, fled from the table and fell into the arms of his father, who was running towards her. But Gregor had no time for his parents now; the chief clerk was already on the stairs; his chin on the banister, he looked back one last time. Gregor took a run to catch up with him as safely as possible; the chief clerk must have suspected something, because he jumped over several steps and disappeared; "Huh!" he screamed, and it echoed through the entire stairwell. Unfortunately, the manager's flight also seemed to completely confuse his father, who had been relatively composed until then, because instead of running after the manager himself or at least not hindering Gregor in his pursuit, he grabbed the manager's stick with his right hand, which the manager had left on a chair with his hat and overcoat, took a large newspaper from the table with his left hand and, stamping his feet, began to drive Gregor back to his room by waving the stick and newspaper. No plea from Gregor helped, no plea was understood, no matter how humbly he turned his head, his father only stamped his feet harder.

Over there, despite the cool weather, his mother had thrown open a window and leaned out, pressing her face into her hands far outside the window. A strong draft arose between the alley and the stairwell, the window curtains flew open, the newspapers on the table rustled, individual sheets of paper blew across the floor. His father pushed relentlessly and hissed like a wild man. But Gregor had no practice in walking backwards; it was really very slow. If only Gregor had been allowed to turn around, he would have been in his room straight away, but he was afraid of making his father impatient by turning around so quickly, and at any moment he was in danger of receiving a fatal blow to the back or head from the stick in his father's hand. But finally Gregor had no other choice, for he realized with horror that he couldn't even keep the direction he was walking backwards; and so he began to turn around as quickly as possible, but in reality very slowly, while continually casting anxious glances at his father. Perhaps his father noticed his good intentions, for he did not disturb him, but even directed the turning movement from a distance with the tip of his stick.

7

If only it hadn't been for his father's unbearable hissing! Gregor was completely lost over it. He had almost turned around when, constantly listening for the hissing, he made a mistake and turned back a little. But when he finally managed to get his head in front of the door, it became clear that his body was too wide to get through without difficulty. Of course, in his current state, it never even occurred to his father to open the other door to make enough room for Gregor. His obsession was simply that Gregor had to get into his room as quickly as possible. He would never have allowed the complicated preparations Gregor needed to make in order to stand up and perhaps get through the door that way. Instead, as if there were no obstacle, he urged Gregor forward with particular noise; behind Gregor it no longer sounded like the voice of just one father; now there was really no fun anymore, and Gregor pushed his way through the door - come what may. One side of his body rose, he lay crooked in the doorway, one of his flanks was completely rubbed raw, ugly marks remained on the white door, soon he was stuck and could no longer move on his own, the little legs on one side hung trembling in the air, the ones on the other were painfully pressed to the ground - then his father gave him a strong push from behind, which was now truly liberating, and he flew, bleeding profusely, far into his room. The door was slammed shut with the stick, then it was finally quiet.

It was only at dusk that Gregor awoke from his heavy, fainting sleep. He would certainly have awoken not much later without being disturbed, for he felt sufficiently rested and well-rested, but it seemed to him as if a fleeting step and a cautious closing of the door leading to the anteroom had awakened him. The light of the electric street lamps lay pale here and there on the ceiling and on the higher parts of the furniture, but downstairs where Gregor was, it was dark. He slowly pushed himself towards the door, still clumsily feeling with his feelers, which he was only now learning to appreciate, to see what had happened there. His left side seemed to be one long, unpleasantly tight scar and he had to limp on both rows of legs. One of his legs had been badly injured during the morning's events - it was almost a miracle that only one had been injured - and was dragging along lifelessly.

Only when he reached the door did he realise what had actually lured him there; it was the smell of something edible. There was a bowl filled with sweet milk with little slices of white bread floating in it. He almost laughed with joy, for he was even hungrier than he had been that morning, and he immediately dipped his head into the milk almost up to his eyes. But soon he pulled it back again, disappointed; not only did he have difficulty eating because of his delicate left side - and he could only eat when his whole body was working with him, panting - but he also did not like the milk, which was normally his favourite drink and which his sister had certainly put in for him for that reason, and he almost turned away from the bowl with reluctance and crawled back to the middle of the room.

In the living room, as Gregor saw through the crack in the door, the gas was lit, but whereas at this time of day his father would raise his voice and present his afternoon newspaper to his mother and sometimes to his sister, now not a sound could be heard. Perhaps this reading aloud, which his sister always told him and wrote about, had recently fallen out of practice. But it was also so quiet all around, although the apartment was certainly not empty. "What a quiet life the family led," Gregor said to himself and, as he stared into the darkness ahead of him, felt great pride that he had been able to provide such a life for his parents and his sister in such a beautiful apartment. But what if all peace, all prosperity, all contentment were to come to a terrible end? In order not to lose himself in such thoughts, Gregor preferred to get moving and crawl up and down the room.

Once during the long evening one side door and once the other were opened just a crack and then quickly closed again; someone had a desire to come in, but also too many reservations. Gregor stopped right at the living room door, determined to somehow get the hesitant visitor in or at least find out who he was; but now the door was no longer opened and Gregor waited in vain. In the morning, when the doors were locked, everyone had wanted to come in to him; now that he had opened one door and the others had obviously been opened during the day, no one came, and the keys were now also in the outside.

The light in the living room was turned off late in the night, and it was easy to see that his parents and sister had stayed awake for so long, because all three of them were now walking away on tiptoe. Nobody would come to see Gregor until morning, so he had a long time to think undisturbed about how he should now reorganize his life. But the high, empty room in which he was forced to lie flat on the floor frightened him, without him being able to find out why, because it was the room he had lived in for five years - and with a half-unconscious turn and not without a slight sense of shame, he hurried under the sofa, where, although his back was a little pressed and he could no longer raise his head, he immediately felt very comfortable and only regretted that his body was too wide to fit completely under the sofa.

8

There he remained the whole night, which he spent partly in a half-sleep, from which hunger kept awakening him, and partly in worries and vague hopes, all of which led to the conclusion that he must remain quiet for the time being and, by patience and the greatest consideration, make the family bearable the inconveniences which, in his present condition, he was compelled to cause them.

Early in the morning, it was still almost night, Gregor had the opportunity to test the strength of his newly made resolutions, for his sister, almost fully dressed, opened the door from the anteroom and looked in with anticipation. She did not find him immediately, but when she noticed him under the sofa - God, he had to be somewhere, he hadn't been able to fly away - she was so frightened that, unable to control herself, she slammed the door shut from the outside. But as if she regretted her behavior, she immediately opened the door again and tiptoed in as if she were visiting someone seriously ill or even a stranger. Gregor had pushed his head almost to the edge of the sofa and was watching her. Would she notice that he had left the milk out, and not because he was hungry, and would she bring in another dish that would suit him better? If she didn't do it of her own accord, he would rather starve than point it out to her, although he was really tempted to rush out from under the sofa, throw himself at his sister's feet and ask her for something good to eat. But his sister immediately noticed with surprise that the bowl was still full, with only a little milk spilled all around it. She picked it up immediately, not with her bare hands, but with a rag, and carried it outside. Gregor was extremely curious to see what she would bring as a replacement, and he had all sorts of thoughts about it. But he could never have guessed what his sister was really doing in her kindness. To test his taste, she brought him a whole selection, all spread out on an old newspaper. There was old, half-rotten vegetables; bones from the evening meal surrounded by solidified white sauce; a few raisins and almonds; a cheese that Gregor had declared inedible two days ago; a dry loaf of bread, a loaf of bread smeared with butter and salt. In addition to all of this, she put the bowl, probably intended for Gregor once and for all, into which she had poured water. And out of delicacy, because she knew that Gregor would not eat in front of her, she left as quickly as possible and even turned the key so that only Gregor would notice that he could make himself as comfortable as he wanted. Gregor's little legs were spinning when it was time to eat. His wounds must have healed completely by now, he no longer felt any hindrance, he was amazed by this and thought about how more than a month ago he had cut his finger very slightly with a knife and how the wound had hurt him enough the day before yesterday.

"Should I have less sensitivity now?" he thought, sucking greedily on the cheese that had immediately and emphatically attracted him above all other foods. He ate the cheese, the vegetables and the sauce in quick succession, his eyes watering with satisfaction. The fresh food, on the other hand, did not taste good to him, he could not even stand the smell of it and even dragged the things he wanted to eat a little further away. He had long since finished everything and was now lying lazily in the same place when his sister slowly turned the key as a signal that he should withdraw. This immediately startled him, even though he was almost asleep, and he hurried back under the sofa. But it cost him great self-control to stay under the sofa even for the short time that his sister was in the room, because his body had become a little rounded from the copious food and he could hardly breathe in the cramped space. With little fits of suffocation, he watched with slightly bulging eyes as the unsuspecting nurse used a broom to sweep up not only the leftovers, but also the food that Gregor had not even touched, as if it were no longer usable, and how she hastily poured everything into a bucket, which she closed with a wooden lid, and then carried everything out. She had hardly turned around when Gregor pulled himself out from under the sofa and stretched and puffed himself up.

In this way Gregor received his food every day, once in the morning when his parents and the maid were still asleep, and the second time after lunch, when his parents were also asleep for a while, and his sister sent the maid off on some errand. They certainly didn't want Gregor to starve, but perhaps they couldn't bear to hear anything more about his food than hearsay, and perhaps his sister wanted to spare them what might only be a small amount of grief, since they were actually suffering enough.

Gregor never found out what excuses had been used to get the doctor and the locksmith out of the apartment that first morning, because since he was not understood, no one, including his sister, thought that he could understand the others, and so when his sister was in his room he had to make do with hearing her sighs and calls to the saints here and there. Only later, when she had gotten a little used to everything - of course there was never any question of her getting used to it completely - did Gregor sometimes catch a comment that was meant in a friendly way or could be interpreted as such. "He did enjoy it today," she would say when Gregor had cleaned up his food properly, while when the opposite happened, which gradually became more and more frequent, she would say almost sadly: "Now everything has come to a standstill again."

9

While Gregor could not hear any news directly, he heard a lot from the adjoining rooms, and if he heard voices just once, he ran straight to the door in question and pressed himself against it with all his body. Especially in the beginning, there was no conversation that did not somehow, even if only secretly, deal with him. For two days, at every mealtime, discussions could be heard about how to behave now; but even between meals, the same topic was discussed, because there were always at least two family members at home, since nobody wanted to stay home alone and they could not leave the apartment completely. On the very first day, too - it was not quite clear what and how much she knew about what had happened - the maid had begged her mother on her knees to let her go immediately, and when she took her leave a quarter of an hour later, she thanked her mother for her dismissal with tears in her eyes, as if it were the greatest favor that had been shown to her here, and, without being asked to do so, made a terrible oath not to reveal the slightest thing to anyone.

Now the sister had to cook with the mother, but that wasn't much of a hassle, because they hardly ate anything. Again and again Gregor heard one of them asking the other to eat, but in vain, and getting no other answer than "Thank you, I've had enough" or something similar. Perhaps nothing was drunk either. Often the sister asked the father if he wanted beer, and she warmly offered to get it herself, and when the father remained silent, she said, to allay any concerns, that she could send the caretaker for it, but then the father finally said a big "No," and no more was said about it.

During the first day, his father explained his entire financial situation and prospects to both his mother and his sister. Now and then he got up from the table and took some receipt or some book of notes from his small safe, which he had saved from the collapse of his business five years ago. One could hear him unlocking the complicated lock and locking it again after taking out what he was looking for. These explanations from his father were partly the first pleasant things Gregor had heard since his imprisonment. He had been of the opinion that his father had not been left with anything at all from that business, at least his father had not told him otherwise, and Gregor had not asked him about it either. Gregor's only concern at the time had been to do everything he could to make the family forget as quickly as possible the business misfortune that had brought everyone into complete hopelessness. And so he had started working with a very special passion and almost overnight he had gone from being a small clerk to a travelling salesman who naturally had completely different opportunities to earn money and whose successes at work were immediately converted into cash in the form of commission, which could be put on the table at home for the astonished and happy family. They had been good times and never again had they been repeated, at least not in such splendour, although Gregor later earned so much money that he was able to cover the expenses of the whole family and did. They had just got used to it, both the family and Gregor, they accepted the money gratefully, he was happy to hand it over, but there was no longer any special warmth. Only his sister remained close to Gregor and it was his secret plan to send her - who, unlike Gregor, loved music very much and knew how to play the violin touchingly - to the conservatory next year, regardless of the great costs that would entail and which would be covered in other ways. During Gregor's short stays in the city, the conservatory was often mentioned in conversations with his sister, but always as a beautiful dream whose realization was out of the question, and his parents did not like to hear even these innocent mentions; but Gregor was thinking very definitely about it and intended to solemnly declare it on Christmas Eve.

Such thoughts, quite useless in his present state, went through his head as he sat there listening to the door. Sometimes he was so tired that he could no longer listen and would let his head hit the door carelessly, but he would immediately hold it back again, because even the slight noise he had made had been heard next door and had silenced everyone. "What is he up to now?" said his father after a while, obviously turning towards the door, and only then did the interrupted conversation gradually resume.

Gregor now learned enough - for his father was in the habit of repeating himself in his explanations, partly because he himself had not concerned himself with these things for a long time, and partly because his mother did not understand everything the first time - that despite all the misfortune, a very small fortune from the old days was still there, which the untouched interest had allowed to grow a little in the meantime. In addition, however, the money that Gregor had brought home every month - he himself had only kept a few guilders for himself - had not been completely used up and had accumulated into a small capital. Gregor, behind his door, nodded eagerly, pleased at this unexpected caution and thrift. Actually, he could have used this surplus money to pay off his father's debt to the boss, and the day when he could have gotten rid of this position would have been much closer, but now it was undoubtedly better the way his father had arranged it.

10

Now this money was not enough to support the family on the interest; it was perhaps enough to support the family for one or two years at most, that was all. It was therefore just a sum that one could not really touch and that had to be put aside for emergencies; but the money to live on had to be earned. Now the father was an old man, although healthy, who had not worked for five years and certainly could not be confident of himself; in those five years, which were the first holidays of his laborious and yet unsuccessful life, he had put on a lot of fat and had become quite clumsy as a result. And the old mother, who suffered from asthma and found even walking around the apartment exhausting, and who spent every other day on the sofa with the window open, having difficulty breathing, was now supposed to earn money? And his sister, who was still a child at seventeen, and who deserved to be granted her previous lifestyle, which consisted of dressing nicely, sleeping late, helping out in the household, taking part in a few modest entertainments and, above all, playing the violin, was supposed to earn money? When the conversation turned to the need to earn money, Gregor always let go of the door first and threw himself onto the cool leather sofa next to the door, because he was all hot with shame and grief.

Often he would lie there all night long, not sleeping a moment, just scratching at the leather for hours. Or he would go to the great trouble of pushing a chair to the window, then crawling up the window sill and leaning against the window, apparently only in some memory of the liberating feeling that looking out of the window had once given him. For in fact, from day to day, he saw things that were only a little way off more and more indistinctly; he no longer saw the hospital opposite, whose all too frequent sight he had previously cursed, and if he had not known for sure that he lived in the quiet but entirely urban Charlottenstrasse, he might have thought that from his window he was looking out into a wasteland in which the grey sky and the grey earth were indistinguishably united. Only twice had the attentive sister noticed that the chair was near the window, when each time she had tidied the room she pushed the chair right back to the window, and even left the inner window sash open from now on.

If only Gregor had been able to speak to his sister and thank her for everything she had to do for him, he would have been able to bear her services more easily; but as it was, he suffered. His sister tried to cover up the embarrassment of the whole thing as much as possible, and the longer time passed, the better she succeeded, of course, but Gregor also saw through everything much more clearly over time. Her very entrance was terrible for him. As soon as she had entered, she ran straight to the window without taking the time to close the door, although she was otherwise careful to spare everyone the sight of Gregor's room, and, as if she were almost suffocating, tore it open with hasty hands, and even when it was very cold, she stayed at the window for a while and breathed deeply. With this running and noise she frightened Gregor twice a day; The whole time he was trembling under the sofa, and yet he knew very well that she would certainly have gladly spared him this, if only she had been able to stay in a room where Gregor was, with the window closed.

Once, a month had already passed since Gregor's transformation and there was no longer any particular reason for his sister to be astonished by Gregor's appearance, she came a little earlier than usual and found Gregor looking out of the window, motionless and in a position that was almost frightening. It would not have been unexpected for Gregor if she had not come in, since his position prevented her from opening the window immediately, but not only did she not come in, she even recoiled and closed the door; a stranger might have thought that Gregor had been lying in wait for her and wanted to bite her. Gregor immediately hid under the sofa, of course, but he had to wait until midday before his sister came back, and she seemed much more agitated than usual. He realized from this that the sight of him was still unbearable to her and would continue to be unbearable, and that she must have had to force herself not to run away from the sight of even the small part of his body that protruded from under the sofa. In order to spare her this sight too, one day he carried the sheet on his back - it took him four hours to do this - onto the sofa and arranged it in such a way that he was now completely hidden and that his sister could not see him even if she bent down. If she had not thought this sheet necessary, she could have removed it, for it was clear enough that Gregor could not enjoy shutting himself off so completely, but she left the sheet as it was and Gregor even thought he caught a grateful look when he carefully lifted the sheet a little with his head to see how his sister was reacting to the new arrangement.

During the first two weeks, his parents could not bring themselves to come in and he often heard them fully recognizing the work their sister was doing, whereas up to that point they had often been annoyed with their sister because she had seemed to them to be a somewhat useless girl. Now, however, both father and mother often waited outside Gregor's room while his sister tidied it up, and as soon as she came out, she had to tell him exactly what the room looked like, what Gregor had eaten, how he had behaved this time, and whether there was perhaps any slight improvement. His mother, by the way, wanted to visit Gregor relatively soon, but his father and sister initially held her back with rational arguments, which Gregor listened to very attentively and which he fully approved of. Later, however, they had to hold her back by force, and when she then called out: "Just let me see Gregor, he is my unfortunate son! Don't you understand that I have to go to him?' Then Gregor thought that perhaps it would be a good thing if his mother came in, not every day of course, but perhaps once a week; she understood everything much better than his sister, who, despite all her courage, was only a child and, ultimately, had perhaps only taken on such a difficult task out of childish recklessness.

11

Gregor's wish to see his mother was soon fulfilled. During the day Gregor did not want to show himself at the window out of consideration for his parents, but he could not crawl much on the few square meters of floor either, lying quietly at night was difficult for him to bear, eating soon no longer gave him the slightest pleasure, and so to distract himself he took up the habit of crawling back and forth across the walls and ceiling. He particularly liked hanging up on the ceiling; it was completely different to lying on the floor; you breathed more freely; a slight swaying went through your body; and in the almost blissful distraction in which Gregor found himself up there, it could happen that, to his own surprise, he let go and hit the floor. But now he had completely different control over his body than before and did not injure himself even with such a great fall. The nurse immediately noticed the new entertainment Gregor had found for himself - he also left traces of his glue here and there when he crawled - and she took it into her head to enable Gregor to crawl to the greatest extent possible and to remove the furniture that prevented him from doing so, especially the chest of drawers and the desk.

But now she was not in a position to do this alone; she did not dare to ask her father for help; the maid would certainly not have helped her, for this girl, aged about sixteen, had waited bravely since the previous cook had been dismissed, but had asked for the privilege of being able to keep the kitchen locked at all times and only having to open it on special request; so the sister had no choice but to fetch her mother once in her father's absence. Her mother came over with cries of excited joy, but fell silent at the door to Gregor's room. First, of course, her sister checked whether everything in the room was in order; only then did she let her mother in. Gregor had hastily pulled the sheet deeper and into more folds, and the whole thing really only looked like a sheet that had been thrown over the sofa by chance. This time, too, Gregor refrained from spying under the sheet; he refrained from seeing his mother this time and was just glad that she had come after all. "Come on, you can't see it," said the sister, and she was obviously leading her mother by the hand. Gregor now heard how the two weak women moved the old, heavy chest from its place, and how his sister kept taking on most of the work, ignoring the warnings of his mother, who was afraid that she would overexert herself. It took a very long time. After about a quarter of an hour of work, his mother said that it would be better to leave the chest there, because firstly, it was too heavy, they wouldn't be able to finish before their father arrived and with the chest in the middle of the room it would block Gregor's every path, and secondly, it was not at all certain that Gregor would be doing himself any favors by removing the furniture. The opposite seemed to be the case for her; the sight of the empty wall downright weighed on her heart; and why shouldn't Gregor have the same feeling, since he had long been used to the furniture and would therefore feel abandoned in the empty room.

"And isn't it the case then," concluded the mother very quietly, almost whispering, as if she wanted to prevent Gregor, whose exact whereabouts she did not know, from even hearing the sound of the voice, for she was convinced that he did not understand the words, "and isn't it the case that by removing the furniture we are showing that we are giving up all hope of improvement and are ruthlessly leaving him to himself? I think it would be best if we tried to keep the room exactly as it was before, so that when Gregor comes back to us, he will find everything unchanged and will be able to forget the intervening period all the more easily."

When Gregor heard these words from his mother, he realized that the lack of any direct human contact, combined with the monotonous life in the midst of the family, had confused his mind over the course of these two months, for he could not explain otherwise how he could seriously have wanted his room to be emptied. Did he really want to have the warm room, comfortably furnished with inherited furniture, turned into a cave in which he would then be able to crawl in all directions undisturbed, but at the same time quickly and completely forget his human past? He was already close to forgetting, and only his mother's voice, which he had not heard for a long time, had shaken him awake. Nothing was to be removed; everything had to stay; he could not do without the positive effects of the furniture on his condition; and if the furniture prevented him from doing this senseless crawling around, it was not a disadvantage, but a great advantage.

Unfortunately, her sister had a different opinion; she had gotten into the habit, not without reason, of acting as a special expert when discussing Gregor's affairs with her parents, and so her mother's advice was reason enough for her sister to insist on the removal not only of the chest of drawers and the desk, which were the only things she had thought of at first, but of all the furniture, with the exception of the indispensable sofa. Of course, it was not just childish defiance and the self-confidence she had recently gained so unexpectedly and with such difficulty that prompted her to make this demand; she had actually observed that Gregor needed a lot of space to crawl around, but, as far as one could see, did not use the furniture in the slightest.

Perhaps the dreamy nature of girls her age, which seeks satisfaction at every opportunity, also played a role, and which now tempted Grete to want to make Gregor's situation even more terrifying, so that she could then do even more for him than she had done up to now. For no one but Grete would ever dare to enter a room in which Gregor alone dominated the empty walls. And so she did not let her mother dissuade her from her decision, even in this room, who seemed unsure because of her restlessness, soon fell silent and helped her sister as best she could to take the box out. Well, Gregor could still do without the box in an emergency, but the desk had to stay. And no sooner had the women left the room with the box, which they were groaning against, than Gregor poked his head out from under the sofa to see how he could intervene carefully and as considerately as possible. But unfortunately it was the mother who returned first, while Grete was in the next room holding the box and swinging it back and forth by herself, without of course moving it. But the mother was not used to seeing Gregor; he could have made her ill, and so Gregor, frightened, ran backwards to the other end of the sofa, but could no longer prevent the sheet from moving a little. That was enough to attract the mother's attention. She paused, stood still for a moment and then went back to Grete.

12

Although Gregor kept telling himself that nothing out of the ordinary was happening, just a few pieces of furniture being moved, he soon had to admit that the women walking back and forth, their little calls to him, the scraping of the furniture on the floor, had the effect of a great commotion, fed from all sides, and he had to tell himself, no matter how tightly he pulled his head and legs to himself and pressed his body to the floor, that he would not be able to endure it all for long. They cleared out his room, took everything he loved; they had already carried out the box containing the jigsaw and other tools; now loosened the desk that had already been firmly buried in the ground, at which he had written his homework as a business graduate, as a middle school student, and even as a primary school student - he really had no time left to examine the good intentions of the two women, whose existence he had almost forgotten, for they were already working in silence from exhaustion, and all that could be heard was the heavy tapping of their feet.

And so he burst out - the women were leaning on the desk in the next room to catch their breath - changed direction four times, he really didn't know what to save first, then he saw the picture of the lady dressed in furs hanging conspicuously on the otherwise empty wall, quickly crawled up and pressed himself against the glass, which held him in place and did his hot belly good. This picture at least, which now completely covered Gregor, was something no one would take away. He turned his head towards the door of the living room to watch the women as they returned.

They hadn't allowed themselves much rest and they were already back; Grete had put her arm around her mother and was practically carrying her. "So what shall we do now?" said Grete and looked around. Then her eyes met Gregor's on the wall. It was probably only because of her mother's presence that she kept her composure, bent her face towards her mother to stop her looking around and said, albeit trembling and without thinking: "Come on, shouldn't we go back to the living room for a moment?" Grete's intention was clear to Gregor; she wanted to get her mother to safety and then chase him off the wall. Well, she could at least try! He was sitting on his picture and wouldn't give it up. He would rather jump in Grete's face.

But Grete's words had really worried her mother. She stepped aside, saw the huge brown stain on the flowered wallpaper, and before she was even aware that it was Gregor she was seeing, she cried out in a shrill, hoarse voice: "Oh God, oh God!" and fell over the sofa with her arms outstretched, as if she were giving up everything, and did not move. "You, Gregor!" cried her sister, with a raised fist and a piercing look. These were the first words she had spoken directly to him since the transformation. She ran into the next room to get some essence with which she could wake her mother from her unconsciousness. Gregor wanted to help too - there was still time to save the picture - but he was stuck to the glass and had to tear himself away by force. He then ran into the next room as if he could give his sister some advice, as in the old days, but then had to stand behind her, doing nothing. While she was rummaging through various bottles, she was still frightened when she turned around; a bottle fell to the floor and broke; a splinter injured Gregor's face, some caustic medicine flowed around him; Grete then, without stopping any longer, took as many bottles as she could hold and ran with them into her mother's; she slammed the door shut with her foot. Gregor was now shut away from his mother, who was perhaps close to death because of his fault; he was not allowed to open the door if he did not want to chase away his sister, who had to stay with his mother; he had nothing to do now but wait; and, plagued by self-reproach and worry, he began to crawl, crawled over everything, walls, furniture and ceiling, and finally, in his despair, when the whole room was already starting to spin around him, he fell in the middle of the large table.

A little while passed, Gregor lay there exhausted, it was quiet all around, perhaps that was a good sign. Then the doorbell rang. The girl was of course locked in her kitchen and Grete had to go and open it. Her father had come. "What happened?" were his first words; Grete's appearance had probably told him everything. Grete answered in a dull voice, evidently pressing her face against her father's chest: "Mother was unconscious, but she's already better. Gregor has escaped." "I expected it," said his father, "I've always told you, but you women don't want to listen."

It was clear to Gregor that his father had misinterpreted Grete's all too brief message and assumed that Gregor had committed some kind of violent act. Gregor therefore had to try to appease his father now, because he had neither the time nor the opportunity to explain things to him. And so he fled to the door of his room and pressed himself against it so that his father, when he entered from the anteroom, could see that Gregor had every intention of returning to his room immediately and that there was no need to drive him back; all they had to do was open the door and he would disappear in a moment.

But his father was in no mood to notice such subtleties; "Ah!" he called out as soon as he entered, in a tone as if he were angry and happy at the same time. Gregor withdrew his head from the door and raised it towards his father. He had not really imagined his father standing there like this; however, because of his new-fangled crawling around, he had neglected to pay as much attention to what was going on in the rest of the apartment as he had done in the past, and he should have been prepared to find things changed. Nevertheless, nevertheless, was this still his father? The same man who had lain wearily buried in bed when Gregor had gone on a business trip in the past; who had greeted him in his dressing gown in an armchair on the evenings he returned home; was not really able to stand up, but only raised his arms as a sign of joy, and who, on the rare walks they took together on a few Sundays a year and on the most important holidays between Gregor and his mother, who were already walking slowly, always worked his way a little more slowly, wrapped up in his old coat, with his cane always carefully placed on his shoulders, and, when he wanted to say something, almost always stood still and gathered his companions around him?

13

But now he was standing upright, dressed in a tight blue uniform with gold buttons, like those worn by bank servants; his strong double chin was visible above the high, stiff collar of his coat; his black eyes were fresh and alert from under his bushy eyebrows; his otherwise disheveled white hair was combed down into a meticulous, shiny parting. He threw his cap, on which was a gold monogram, probably that of a bank, across the room in an arc to the sofa and walked towards Gregor with the ends of his long uniform coat thrown back and his hands in his trouser pockets, with a grim expression on his face.

He probably didn't know what he was planning to do; he did lift his feet unusually high, and Gregor was amazed at the gigantic size of his boot soles. But he didn't stop there, he knew from the first day of his new life that his father only considered the greatest severity appropriate towards him. And so he ran ahead of his father, stopping when his father stopped, and rushing forward again when his father even moved. They made several circuits around the room without anything significant happening, and without the whole thing having the appearance of being pursued because of his slow pace. So Gregor stayed on the floor for the time being, especially since he was afraid that his father might think that running to the walls or ceiling was particularly wicked. But Gregor had to tell himself that he wouldn't be able to keep up this running for long, because while his father took a step, he had to make countless movements. He was already beginning to feel short of breath, as he had not had completely trustworthy lungs in his earlier days. As he staggered along, trying to gather all his strength for the run, barely keeping his eyes open; in his stupor he did not even think of any other way of escaping than by running; and had almost forgotten that the walls were open to him, although here they were covered with carefully carved furniture full of spikes and points - when something flew down just next to him, lightly thrown, and rolled in front of him. It was an apple; a second one flew after it immediately; Gregor stopped in shock; it was useless to keep running, because his father had decided to bombard him.

He had filled his pockets from the fruit bowl on the sideboard and was now throwing apple after apple, without aiming carefully. These small red apples rolled around on the floor as if they were electrified and bumped into each other. A weakly thrown apple brushed Gregor's back, but slid away harmlessly. One that flew immediately after it, however, literally penetrated Gregor's back. Gregor wanted to drag himself on, as if the surprising, unbelievable pain could disappear with a change of location; but he felt as if he were nailed to the ground and stretched, his senses completely confused. Only with his last glance did he see how the door of his room was thrown open and his mother rushed out in front of his screaming sister, in her shirt, for his sister had undressed her to give her some breathing room in her faint, how his mother then ran towards his father and on the way his untied skirts slid to the floor one after the other, and how she stumbled over the skirts and rushed towards his father and, in complete union with him - but Gregor's eyesight was already failing - with her hands on the back of his father's head, begged for Gregor's life to be spared.

Gregor's serious injury, from which he suffered for over a month - the apple remained in his flesh as a visible souvenir, since no one dared to remove it - seemed to have reminded even his father that Gregor, despite his present sad and disgusting appearance, was a member of the family who should not be treated like an enemy, but towards whom it was the commandment of family duty to swallow one's revulsion and to tolerate, nothing but to tolerate. And even though Gregor had probably lost mobility forever as a result of his wound and needed long, long minutes to cross his room like an old invalid - crawling at heights was out of the question - he found that this worsening of his condition was compensated for in a way that was, in his opinion, completely sufficient by the fact that the living room door, which he had been watching closely for an hour or two beforehand, was always opened towards evening, so that, lying in the darkness of his room and invisible from the living room, he could see the whole family at the lighted table and listen to their conversations, as it were with general permission, and in a completely different way to how he had been before.

Of course, these were no longer the lively conversations of the past, which Gregor had always thought of with some longing in the small hotel rooms when he had had to throw himself tiredly into the damp bedclothes. Now it was mostly very quiet. Soon after dinner, his father fell asleep in his armchair; his mother and sister admonished each other to be quiet; his mother, leaning far under the light, sewed fine linen for a fashion store; his sister, who had taken a job as a saleswoman, learned shorthand and French in the evenings so that she might get a better job later. Sometimes his father woke up and, as if he didn't even know he had been sleeping, said to his mother: "You've been sewing for so long today!" and immediately fell asleep again, while his mother and sister smiled wearily at each other.